Modern life unfolds at a relentless pace, driven by imperatives like “next,” “faster,” and “simultaneous.” In such a landscape, the simple act of pausing—to anchor oneself in the present—has become a quietly profound form of luxury. Meditation, deep breathing, and communion with nature are some of the paths to this stillness. Yet one of the most accessible and overlooked avenues is the act of eating itself. In Japanese culinary culture, this idea is not merely philosophical—it is embedded deeply into the structure of the meal.

Mindfulness is the art of presence: focusing one’s awareness not on past regrets or future anxieties, but on the sensations of the current moment. It is a return to the senses, allowing the mind to rest and the body to realign. Eating, in its purest form, is a sensory ritual—an opportunity to engage with sight, smell, taste, and touch. Yet in the rush of daily life, meals often become distracted affairs, overshadowed by screens, conversation, or haste.

Japanese cuisine offers a quiet counterpoint to this tendency. Through its rituals and formality, it gently guides the diner back to presence. The simple gesture of placing hands together and saying itadakimasu before a meal is not just etiquette—it is a moment of gratitude and a mindful gateway into the act of eating. In those brief seconds—hands together, eyes on the plate, breath steady—one reconnects with the food, the source, and the self.

In Japanese cuisine—particularly in refined formats such as kaiseki or kappo—it is rare for all dishes to arrive at once. Instead, each course is presented in succession, allowing the diner to focus entirely on a single plate, a single set of flavors, a single moment. Every course introduces new ingredients, a different preparation method, and often a distinct vessel. This progression invites a quiet attentiveness—an experience that might be best described as meditation through dining.

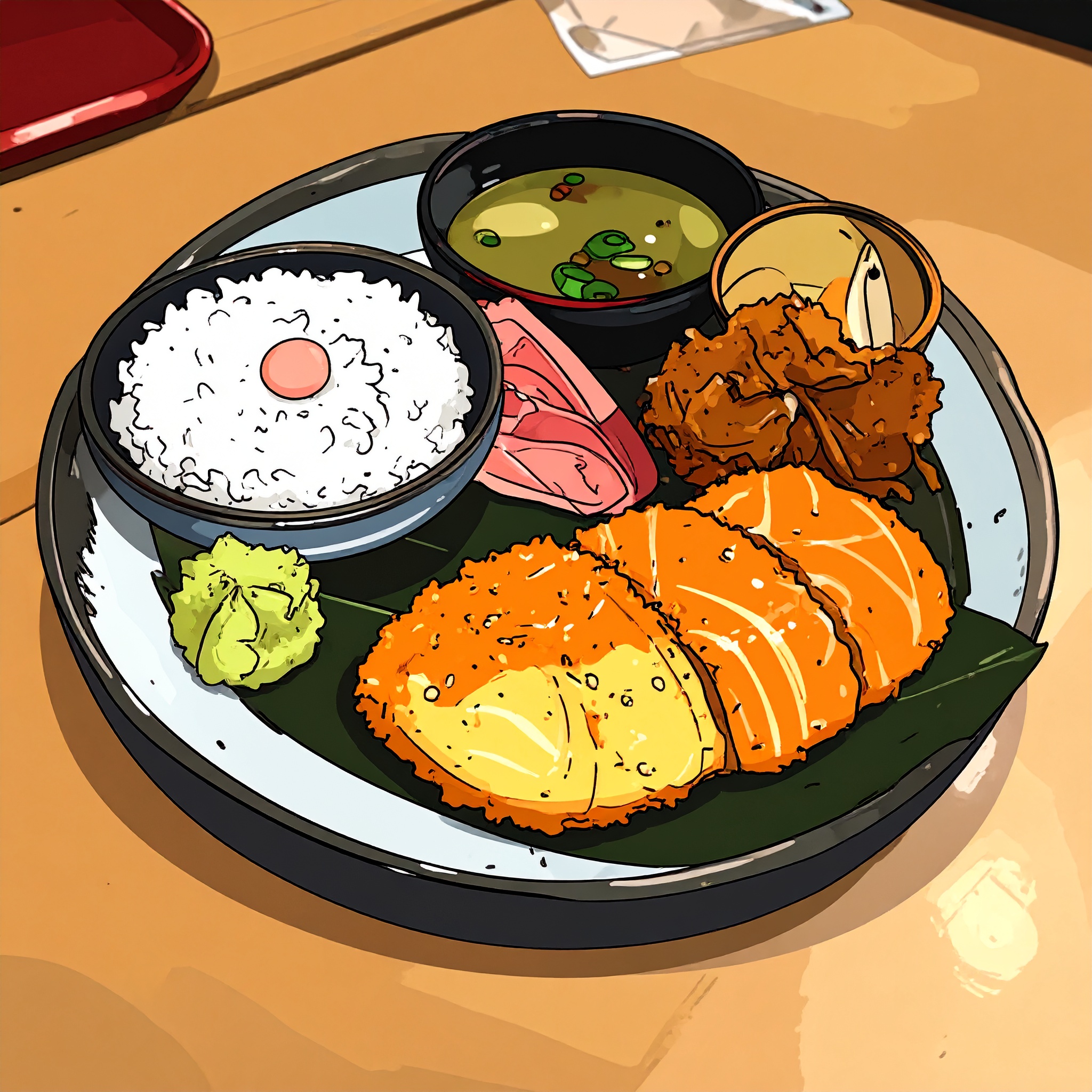

Plating, too, is intentionally composed to foster stillness. Nothing is overfilled; generous use of negative space draws the eye inward, highlighting the elegance of each ingredient. The careful balance of the five traditional colors—red, green, white, yellow, and black—alongside seasonal garnishes and harmonious vessels, is no coincidence. These visual cues guide the senses toward the present, softly ushering awareness into the here and now.

As the meal begins, the sensory tapestry unfolds. The rising steam from freshly cooked rice, the gentle aroma of dashi, the subtle sound of chopsticks meeting porcelain, the warmth that greets the lips, the textures that dissolve on the tongue—each sensation, if acknowledged, brings the diner deeper into the immediacy of the moment.

Integral to the Japanese dining experience is a sense of silence—not as absence, but as presence. There is no background music, no elaborate storytelling. Instead, the space honors the unspoken, allowing the cuisine itself to communicate. The chef’s movements are composed, purposeful, and quiet. The guests, too, engage with calm and attentiveness. This stillness creates a sanctuary, a pause in the noise of the outside world, where one can recalibrate mind and body.

Traditional meal structures such as ichiju-sansai (one soup, three side dishes) or ichiju-issai (one soup, one side) are particularly relevant from a mindfulness perspective. Celebrated for their nutritional balance, these formats also invite a retreat from overchoice. They teach restraint and presence—offering only what is essential, in just the right measure. A single vegetable dish seasoned only with salt, a broth made simply from kombu and bonito, freshly steamed rice fragrant in its purity—these are not minimalist for austerity’s sake, but to awaken the senses. In simplicity, subtlety becomes visible. Each nuance is perceptible, and the act of eating becomes a study in texture, temperature, and aroma.

At the conclusion of a Japanese meal, the phrase gochisousama is quietly spoken. This simple yet profound expression carries dual significance: gratitude to those who prepared and served the food, and a moment of internal closure—marking the end of the dining experience with intention. Together with the initial offering of itadakimasu, this closing ritual frames the meal within a mindful arc, where eating is never unconscious, but fully present.

In this way, mindfulness is not something added to Japanese cuisine—it is embedded within it, both culturally and structurally. Rather than stimulating focus through excess, the experience removes distractions, guiding the diner gently toward awareness of this one bite, in this one moment. This clarity not only enhances physical enjoyment, but also nourishes emotional well-being, often leaving the diner with a lasting sense of calm and quiet satisfaction.

In a world overwhelmed by information, where efficiency and speed often take precedence, meals can too easily become mere tasks—or background noise to a busier narrative. Yet Japanese cuisine offers a quiet counterpoint: a proposal to return eating to the center of our attention.

To focus on a single bite, to sense the season in a bowl of soup, to feel the presence of the maker behind the vessel—these acts gently restore the experience of dining as one of connection, reflection, and healing. In this mindful engagement, the meal becomes a moment of restoration—an invitation to reconnect with oneself. To eat is to meditate in the most accessible way. And Japanese cuisine may be one of the most beautiful instruments we have for such meditation.